Living in the Song—The Wolf Bros. Live in Colorado

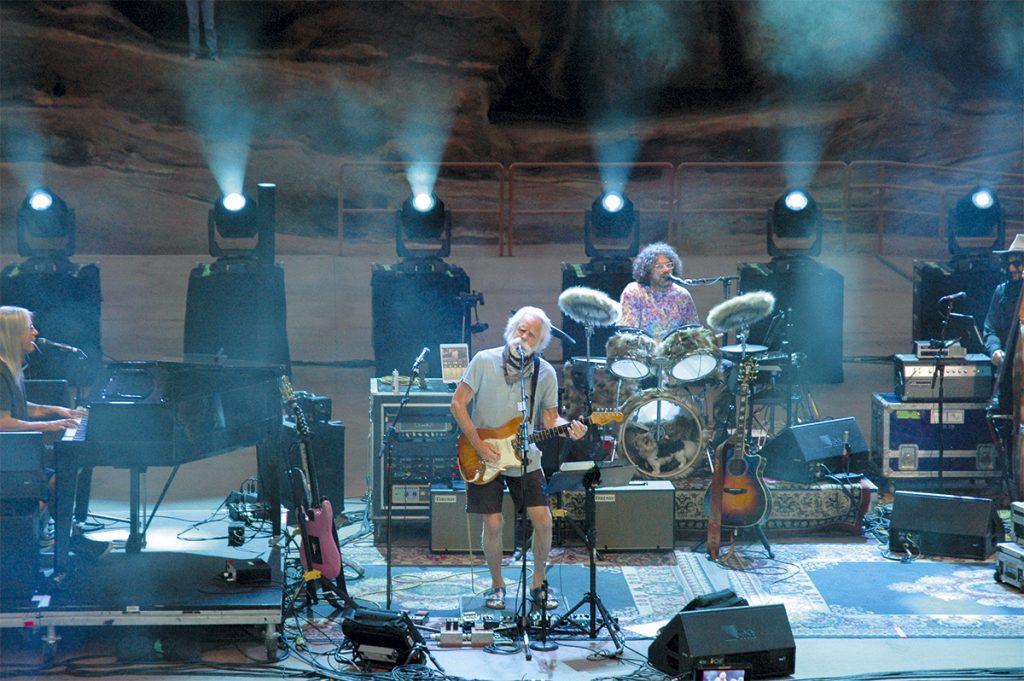

Since even before The Summer of Love, Bobby Weir has fronted every incarnation of the Dead in addition to a myriad of other projects. In 2018 he began touring with a trio dubbed The Wolf Bros. featuring Jay Lane on drums and legendary producer Don Was on upright bass. This trio has since expanded to a ten-piece ensemble with Jeff Chimenti on keyboards and Greg Leisz on pedal steel guitar, along with the Wolf Pack: Brian Switzer (trumpet), Adam Theis (trombone), Sheldon Brown (saxophone, clarinet, flute), Mads Tolling (violin, viola) and Alex Kelly (cello). Like most current Dead-related projects, almost every show of every tour is available to instantly stream and download. Live in Colorado breaks that ‘live off the soundboard’ mold, offering fans a chance to experience select songs from the band’s recent Red Rocks run, lovingly mixed and available on vinyl, CD, and via download. We sat down with Bobby and Don to learn more.

Bobby Weir

Bobby Weir

Thanks to the Dead’s live recording culture, you may be one of the most recorded musicians of all time. Are you conscious of that when you go on stage?

Not at all. When I go on stage, I go into a world where the characters in the songs live, and I try not to think about technical stuff at all.

When did you decide that the Red Rocks shows would become an official album?

Because of the nature of our setup, we can record any show, and we just assumed that if the band played well, and it did, we’d make a record out of it.

Do you typically record every performance as a multitrack?

Yes, it’s a good reference for us when we get around to listening to it, which we don’t do all that much, at least I don’t—I think Don actually does.

I’ve often wondered, do you guys get back on the bus and go, “Hey, let’s listen to the show we just did 20 minutes ago?”

We used to do that in the old days with the Grateful Dead, and it helped to grow us as a band because you can hear what’s working and what’s not. With the Wolf Bros., we get together and listen back to our performances every now and again, just to stay sharp.

You guys played 34 songs between the two nights. How did you whittle that down to eight for the album?

Don did that. He’s our resident bigshot producer. [laughter] He knows what works and what doesn’t. My view is a little too subjective, and he’s past that. He picked the songs, presided over the mix, and did what a producer does.

Who does the live recording?

Our front-of-house mixer, Derek Featherstone. I dare say he’s the best in the business. He’s lashed it up so that all he has to do is press the red button, and we’re recording.

We always pan everything where it was on stage because you’re going to get better phase integrity. The band more or less mixes itself. If I need to step out with my guitar at some point, I just crank it.

Were there any moments at Red Rocks that you walked away and said, “Yeah, this is the night!”

I regularly have moments on stage when the character in the song makes some sort of revelation to me. The character is using my voice, my mannerisms, and my hands to tell a story, and every now and again, he’ll show me a new aspect of his character, and I’ll lean into that. That’s what’s going on in my head when I’m performing.

What is your current guitar rig?

I try to keep things as simple as possible. I don’t use much in the way of guitar effects anymore. My current guitar rig is just a little Vox Night Train amplifier. They don’t make them anymore, but I’ve got a few of them. It gives me the high end I’m looking for and goes into distortion very evenly and predictably. From the Night Train, I go into a Universal Audio OX box, and I use a bit of reverb and sometimes a little bit of compression. I’ve been finding that the sounds I get from my guitar are so rich and varied that I don’t need delays. I don’t need phasing. I don’t need flanging. If you let it, the guitar will reveal its subtlety, and that subtlety works with the characters that are coming through me, so they can just tell their story. Wolf Bros. is a ten-piece outfit, so I can’t be playing with delays because that just complicates things and makes the sound too thick.

Are you miking a cabinet on stage?

I don’t mic the cabinet. I’m going direct out of the OX box. I use a Friedman full-range speaker on stage that’s pretty damn flat, and it’s not real big. I use two of them because I’ve been running stereo, but I think I might cut my whole rig back to just mono and just one Friedman

cabinet because I just don’t need stereo anymore.

How do you feel your sound has evolved over the years? Do you feel like you have distinct periods of sound?

Oh, yeah, of course. All guitarists do. Right now, I am going through a purity period. I’m just playing the guitar and letting it tell me what it wants to do. I use a lot of treble in my settings. I crank it almost all the way. Those Vox amplifiers have a bright circuit in them, and I use that. Then I push the front end just a little bit, but not a whole lot—I’m not a chainsaw guitarist. [laughs]

Over the years, I evolved to where I can find so much variety just with my pickup selection and changing guitars. I don’t have specific guitars for different songs; I change guitars when I feel like it. I have some old Gibson guitars that I’m playing that have P90 pickups in them. They’re real bright, and that’s a fun sound because the neck scale is shorter, which means you get a little more fundamental in the overtone series. Then I use a Strat, and the neck scale is longer so you get a richer overtone series and the clang of cold steel. Then I’ve got my D’Angies. [Bobby plays multiple signature D’Angelico guitars, including the new Bedford model. [-Ed.] I’m still working on the solid body, and I haven’t got that where I want it. In the thin body, I’m using Gretsch-style electromatic pickups. The combination of the chambered thin body and those pickups has a real signature sound to it. Again, all the sounds that I use are really bright. I don’t have a tone control on my guitar, I just leave it all the way open. If I want a different tone, I do that with my hands and the way I pick the strings. I want a sound that isn’t thick but is rich and complex. Playing with a ten-piece band, I try to find a sound that doesn’t take up much room sonically.

What are you using for an acoustic?

The acoustic is interesting. I’m still playing around, but I use a small DPA microphone inside the guitar. Where you mount it is critical and also arbitrary. [laughs] Then I also use a bridge pickup. I cut all the low end out of the microphone and all the high end out of the pickup. In bridge pickups, the high end sounds awful. It’s fingernails on a blackboard to me. But the microphone inside the guitar hears the rich high end from the sides and back and what comes out of the soundhole. So, I use the high end from the microphone and the low end from the pickup. This way, you don’t get the low-end feedback that microphones typically give you, and you don’t get the fingernails on the blackboard high end from the bridge pickup. It falls together, and it sounds like a great big acoustic guitar. It’s a complicated system, but I’m trying to simplify it so that we can install it in an acoustic Weir-model D’Angelico we’re working on. I’m really proud of that.

Do you have a favorite vocal mic?

I’ve got a project coming up where I’m playing live with a symphony orchestra, and I might try using one of my large diaphragm tube condenser mics—the old guys, because you get a really warm low end from those. Or I might get a reasonable facsimile of the old ones that you just don’t dare take on the road as they’re just too delicate to travel with. Live I am using a Sennheiser e 935.

What do you use for monitoring on stage?

I’m using a whisper of footlight monitor, but Wolf Bros. play pretty quietly on stage, and I like to go on what I’m hearing back from the room. In-ear monitors have never really worked for me. They’re just really deeply unsatisfying. When I’m playing with Dead & Company, I like to use two Bose towers, and we put them behind me. For some reason, I can’t tell you why, they don’t feed back. We keep them at a reasonable level, and Dead & Company doesn’t play that loud on stage anyway. It adds a little definition to what I’m getting back from the house, which is all I need.

Tamalpais Research Institute (T.R.I.) is a hybrid studio/live broadcast venue. Has your work there informed your live work?

Oh yeah! There’s a lot of back and forth. They are different regiments, but there’s a lot of cross-pollination that goes on.

I remember when you demoed the Meyer Sound Constellation system at T.R.I. a few years back.

I should probably explain the Constellation system. It’s an array of eighty 4″ speakers in a soffit around the front, back and sides of the studio room, along with a couple dozen full range microphones that hang down into the room. They hear everything that’s happening in the room and, through signal processing, play it back to sound like rooms that we’ve shot the response characteristics of. What we did was, we went and shot the response characteristics of various venues, and then we programmed them into the system so that we could have [the sounds of] the Concertgebouw or Carnegie Hall. You can turn the lights down, bring up Grace Cathedral, and it sounds like you’re there in a cathedral. It’s really kind of jaw-dropping.

I remember, it was incredible and clear no matter where you were standing in the space. You had the drummer start playing a groove to the slap-back, and it turned into the groove of ‘West L.A. Fade Away’.

In a lot of the rooms, we shot the response characteristics from the stage, and the balcony presents a parabolic reflective surface. So, you get a hard slapback echo, but with the Constellation system, we can tune that hard echo and have the leeway to bring it forward or back a couple hundred milliseconds. If you tune it to a rhythmic interval, that slapback just reinforces the groove like crazy, like ‘West L.A. Fade Away’, and it’ll also keep the players in time.

Another great thing about that is, if a player’s hearing any sort of delay on their instrument, they’re going to tend to play less. And if you’re a producer, that’s gotta be music to your ears. [laughter]

I’ve always been curious about your original home studio where the Grateful Dead recorded Blues for Allah. How the hell did you guys fit everybody in there?

[Lots of laughter] It was a shoehorn job for sure! Phil was of the opinion at the time that his rig had to be enormously loud—he’s still of that opinion, I think. So, we put his speakers underneath, [the studio] in the garage. And of course, the neighbors had a little something to say about that, but we worked it out with them.

I did a lot of overdubs on subsequent albums in there, but the only major album done there front to back was Blues for Allah. The amount of traffic that brought to the house was… you know, you’re not going to live in peace. After we were done with Blues for Allah, I repurposed the studio for overdubbing and as my office and hangout. We watch movies in there.

Being on the road so much, do you get much studio time now?

I’m in the studio a lot. I’m working on a project now with Giancarlo Aquilanti that is going to feature a full symphony orchestra. Right now, we’re working with Finale to generate MIDI from the score. We were using Pro Tools, but we moved to Logic. Now we’re thinking about moving the whole project to [Universal Audio] Luna. We’re going to see if Luna, being a newer medium, might sound better.

Luna is pretty cool because it has the modeled analog summing.

I think they’ve done their homework. It gives me shivers to think of what it might sound like if we can get the full orchestral recording done in Luna, and I just don’t know if there’s a facility available where we could do it all analog to tape. That would be the best sound, but nobody does that anymore.

So, it sounds like you’re still an analog guy when you can be?

Come on… you can’t beat analog—who has?

Is there any particular song right now that you love night after night? Or is there a song that the fans want to hear but you’re tired of?

The answer to both questions is no. They truly are new every night. Sometimes, a song that I’m not looking forward to steps up, bites me on the ass and says, pay attention! And sometimes, a song that I was really looking forward to goes into a flat phase of its existence. You never can tell when that’s going to happen. All the characters in the songs are multidimensional. As I get to know them and they get to know me, they start divulging new facets of their character and reality—it’s fascinating.

This has been awesome. I really appreciate it.

Thanks, you bet.

Don Was

Don Was

Considering all of the hats you have worn over the years, musician, songwriter, producer, what is it like getting on a bus and hitting the road as the bass player of the Wolf Bros.?

I love it. If you were to chart the entirety of my life, that one wins. I’ve been a bass player longer than anything else. Going out and playing gigs is probably the most natural thing to me and makes me feel at home.

Describe your role as a producer in the Wolf Bros.

Bobby is an incredible guitar player, and he always takes you by surprise, but the whole thing is about his singing. How do you play a song for 40, 50 years? You do it by approaching it with a beginner’s mind every time and finding a new way in.

It’s about giving Bobby the room so that he can tell the story in a fresh way. Every single note I play is played in relation to his singing. If I’m restricting his phrasing in any way, I’ll leave the space. The challenge is to play as little as possible and still be musical and advance the song.

I produced this album the same way. It was about his vocals and turning down the things that were in the way. Making the record was not different than making a Bonnie Raitt record or Willie Nelson record. It’s all about the vocal, and everything else is there to support that.

How did you select and sequence the eight songs on the record from both nights’ performances?

There are two albums, actually. There’s a part two that’ll come out later this year. There are certain underpinnings to any set that we do or Dead & Company does. There is a structure to those sets, and songs tend to work best in one or two different slots. It’s not just randomly calling songs. There’s a dynamic to everything, and we tried to keep that dynamic in place. It’s not that a song was third one night, so it’s third on the album, but if you listen to the albums back to back, it feels like going to a show.

Was anything done differently to record these shows?

It was just a feed off the PA line. All the mics are recorded individually to Pro Tools at front of house, and nothing extra was put up for the sake of recording.

I understand the culture of taping shows and listening back to them, but I’m not personally a fan of it because it doesn’t sound like what I’m hearing, where I’m standing, and it’s always kind of a letdown. I’m a record maker, and I believe you go the extra mile and give people something that will bear the scrutiny of repeated listening.

What was your role in mixing?

My role was just making notes about where things should come up and where they should go down. I was present, but there were two different mix engineers. The first album was mixed by Derek Featherstone, who does front of house for Dead & Company and understands the balance of the Grateful Dead and all its derivatives. The second half was mixed by Elliot Scheiner. Even though the two have a completely different approach, it absolutely flows organically between the first record and the second record. Probably if I didn’t mention it, no one would notice, but I love the fact that one comes from the front-of-house guy and one comes from one of the greatest mixer / producers of all time.

I assume Derek does the mixes for the stream and online downloads. What was different in this mix?

The board mix reflects the levels necessary for the PA. So, for example, if we’re in a really live theater and the drums are really loud and bouncing off the wall, then they turn them down at the PA because there’s already enough in the room. That doesn’t necessarily reflect a great representation of the show. It represents what was necessary to do with the PA to make the room sound balanced.

Was the album mixed in Pro Tools?

Derek mixed it in Pro Tools, Elliot used Nuendo.

Was any of it mixed through analog gear?

Yes, we mixed it while Dead & Company were rehearsing at Henson Studios in L.A. John Mayer has a set up there, so we used John’s room, and he had an API board.

Also, we did a bunch of live streams at T.R.I. last year. We did one a month for maybe six months, and Derek refined the sound for the live streams, which comes through in this album.

I got to see Bobby give a presentation at T.R.I. a few years ago of his Meyer Constellation system, and it was amazing how you could hear everyone in the band clearly no matter where you were in the room.

He loves that, that system. Bobby’s interesting because he comes from almost a pre-monitor era.

He said he uses as little monitoring level on stage as possible and prefers to hear the natural instruments.

He likes to sing to the reverb of the room. There have been times we’ve sound checked, and we see what the slapback time is of the venue, and it’ll affect the tempos we play. He’ll call them off so that it’s slapping back from the rear wall in rhythm.

You’re playing upright on the album. What’s your setup?

I’ve never picked up an electric in the history of the Wolf Bros. The bass itself is weird. It’s a 200 year-old English Church bass. There were originally only three strings, and it’s like a 5/4 size. It’s huge. It actually causes physical pain just to wrap your arms around. It fucked up my shoulder from playing it for a few years, but it’s got this great sound, which I’m not sure anyone really gets to hear. [laughs] Live, you can’t just mic it because it gets too many drums and other stuff.

I use it on sessions, and it’s just a beautiful sounding bass. On stage, I have two David Gage pickups. I have the copper one that goes under the bridge and one in the height adjuster on the bridge. Then I combine the two and plug them into an Ampeg SVT, which is not the usual amp you use for string bass, but I love the way it sounds. That gets miked with an [Electro-Voice] RE20.

What about some of the other instruments?

Each one of them has their own setup. Alex Kelly, the cello player, has a whole footboard of crazy effects. There’ll be many times in this record where you’re going to hear something that you think is the pedal steel or another guitar and it’s cello through effects, and the viola/violin player Mads Trolling, he’s also got some pedals.

Obviously, there’s a lot of bleed when recording a live album. Is that ever frustrating?

You make it part of the thing. The excitement is actually coming from the house. I’ve done a bunch of live records, and some are so crisp they could be studio albums, and there are some that really get the hall into the mix. I prefer the latter. Especially something like this where this circular energy exchange happens with a Grateful Dead-type audience, they’re really like part of the band, and we feed off that energy. You really need to capture that. To only capture the stage does not give you the experience. So, we use a lot of the hall and audience mics at front of house and on the side of the stage. That, of course, limits things later because you can’t really punch in too much. If there’s a huge mistake, which does happen, we’ll pull it back in the mix. And there were technical problems all the time. We actually stopped the show at one point because Jay Lane’s bass drum was distorting and breaking up. You’ve got to fix stuff like that, so there is some fixing.

You rode the technology wave of synths and samplers in the 80s. What technology excites you now?

I just got something called the [LR Baggs] Voiceprint DI. It’s a direct box for an acoustic guitar. But first, you use a microphone in front of the guitar, and it takes an impulse response, like a sonic photograph of the actual guitar and then emulates that in the direct box. David Ryan Harris was using it on his acoustic on this thing we did with John Mayer, and you couldn’t tell that we were using the direct pickup. It sounded like a microphone in front of a really great guitar in the room. I just bought it. I haven’t had a chance to use it yet, but I’m going to take it to rehearsals next week for the March tour. I love this stuff, I keep up with everything that’s out there, but I still think the most important thing is, write a good fucking song! I’m not seeing any devices that compensate for that. [laughter]

What does the word ‘producer’ mean to you?

I like being an intermediary between the artist and the creative ether. You don’t pull the ideas down for them, but you help them capture and develop what they’re hearing in their heads.

Sometimes they may not be able to describe it. They might tell you, I want it to be more orange. You have to figure out what that means and help them realize their vision by whatever means necessary. I mean, I can make my own records if I want to and come up with all the parts, but I personally prefer being surrounded by people whose ideas blow my mind. If we’re reliant on my ideas to carry the record, we’re fucked. [laughs] The highest compliment I can get as a producer is when an artist will say, “That is everything I was hoping for and then some, thank you!” That’s a hit record to me. Whether it sells or doesn’t sell, that’s my first and foremost goal.

Any final thoughts?

If there’s one takeaway from this new album, I want people to go, wow, Bobby’s really singing great. I think he does every night, but now you really get to hear it.

I think his singing now may be the best of his career.

I agree!

Don, it was great talking with you.

Pleasure to speak with you.