Take the fear out of learning to mix “in the box” with these strategies

By Joe Albano

Mixing… well, that’s a bottomless pit of a subject if there ever was one! As I sat down and thought about how my own approach to mixing had evolved over the years, I realized that the single biggest change I had made was moving from traditional console-based mixing (on classic hardware mixing boards) to the powerful but often challenging world of virtual mixing, using the software-based mixer and effects within my digital workstation (Apple Logic Pro on the Mac).

As I made that transition over several years, it’s resulted in a number of changes from the way I used to mix in the analog days of yore—some of these changes in working style were smooth and gradual, while others required much more of an adjustment. Since a lot of folks are making this same transition these days, I thought I’d mention just a few of these adjustments and shifts in technique I adopted when I stepped through the looking glass into the virtual studio.

On Mixing

- The Dirty Knobs — Recording Wreckless Abandon

- Remixing John Lennon

- Vance Powell On Mixing The Raconteurs’ Help Us Stranger

- Steinberg Cubase Power Tips With Sound Designer Robert Dudzic

- On Mixing

- The Art Of Cooking Up A Good Mix!

- Tracking and Mixing for Solid Lows

- Observations On Mixing

- 10 Tips for Better Low End

- Multiband Dynamics

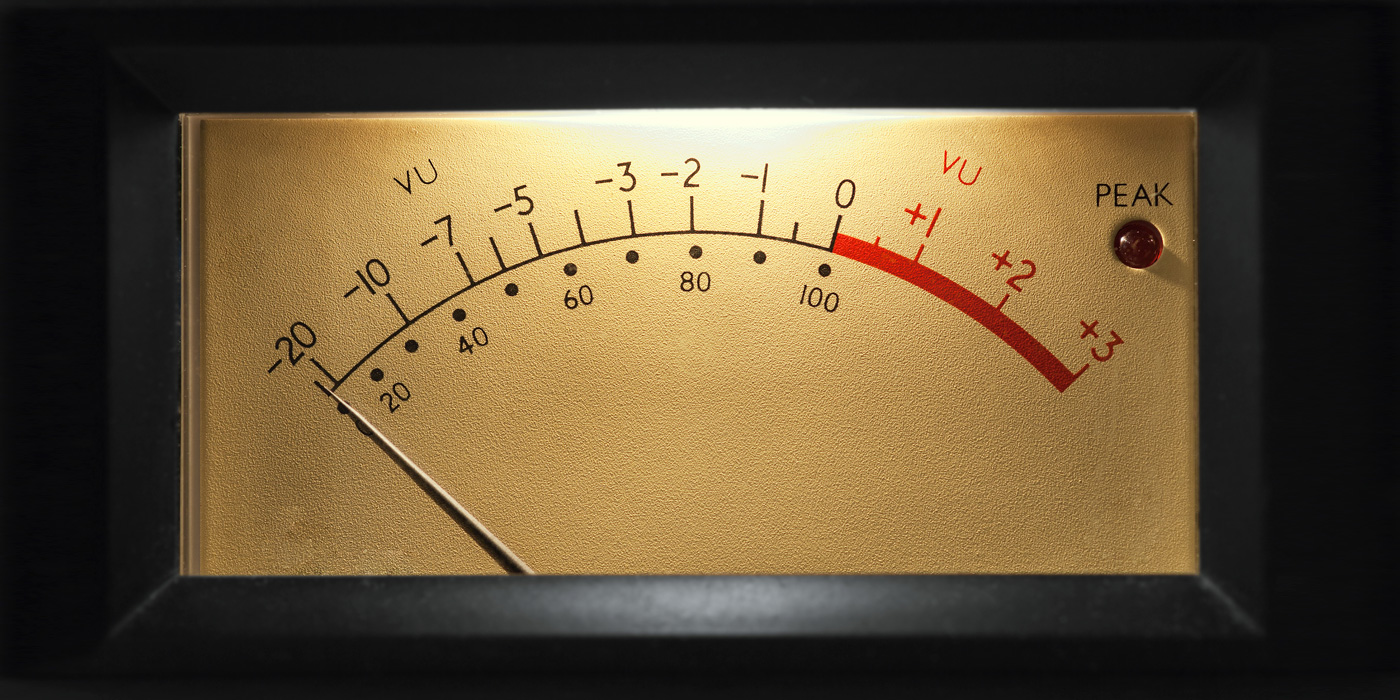

Metering—analog and digital

The difference in metering and calibration between digital and analog systems was one of the things it took me a while to get used to when I first approached virtual mixing. As you may know, analog signals are usually referenced to VU meters that indicate the maximum clean level of steady-state signals (i.e. sustained tones). An indication of 0 VU (more often than not referenced to +4 dBu) marks this point, and the meter is calibrated in dB above and below it, typically from –20 to +3. Sustained signals will be clean up to 0 VU, and progressively more distorted above it.

However, musical signals also contain attack transients, the brief (~15-20 ms) impact noise at the beginning of a percussive sound. These transient peaks may exceed steady-state levels by up to ~20 dB (!) but, because they are so short, they will not be perceived as distorted, and can be safely passed at levels up to +18 to +28 dB above 0 VU. A VU meter’s needle won’t track these peaks, but they’re there with any percussive impact.

Normally, a mix hovering at around 0 VU on a VU meter is at the strongest clean level possible, an average level, with (unseen) peaks extending into the headroom (a sort of safety margin) between 0 VU and the maximum peak level of that system. Maximum peak here stands for the level at which a signal is badly distorted and its waveform clipped when limitations of the circuits are exceeded.

In digital systems things work a little differently. All levels are measured down from, and referenced to, the digital maximum peak level (commonly called 0 dBFS where “FS” stands for Full Scale, where all the bits in a digital word are 1 and there’s nowhere left to go)—there is no functional equivalent to the average level of 0 VU. The reason for this is that even average (sustained) digital signals remain clean all the way up to that maximum peak level.

While analog systems have gradually distorting average levels above 0 VU and can tolerate short peaks up to 20 dB above the average levels, in digital systems sustained signals and transient peaks are the same—both equally clean up to the maximum peak level, and then totally clipped above it. All digital levels are calibrated in –dB values below the maximum of 0 dBFS.

In practice

This difference results in some practical issues when you start to mix in the digital domain. First off, since there is no “average vs. peak” distinction (as far as signal level goes), setting the overall level of a virtual mix will be done referenced to maximum peaks rather than average musical levels—digital meters will typically show peak levels as opposed to average levels.

Despite the difference in calibration, both analog and digital faders are usually calibrated with similar gain markings (unity gain at 0 dB, down to –60 or -∞, up to +6 or +10). But in the digital system, the top of the range is really the top, whereas in analog, there’s probably more peak headroom above. As a result, familiar fader level settings from analog mixes often result in digital overloads—typical working fader levels (or the master output level) may have to be reduced when strong transients are present, to achieve the proper operating levels.

Now, it may occur to the more digital-savvy readers that if you run your mix at slightly lower levels, you could be wasting precious bits of digital resolution. Fortunately, in most workstations mixing is carried out at a much higher resolution (typically 32-bit floating point or 48-bit linear) than the recorded audio files themselves (16- or 24-bit linear). While there is no consensus over whether it’s better to keep track faders low or reduce the level of the master fader, either way you should still have a suitably clean high-resolution signal.

Digital to analog

Transferring a mix out of the digital domain back to analog for any reason could also result in level issues. In a digital mix, if the music does not have many strong transients (i.e. organ music), sustained levels can be pushed right up to the peak ceiling without any penalty. But transferring such a “hot” mix to analog at unity gain might result in sustained (average) levels well above 0 VU, resulting in distortion.

To calibrate your digital and analog systems for set-and-forget levels for transfers or analog monitoring, you could do the following:

• Determine the headroom of the analog electronics (say, for example, a maximum peak level of +18 dB above 0 VU, typical of small mixers);

• Subtract that headroom from 0 dBFS (in this case, for a level of –18 dBFS) to determine a digital level equivalent to 0 VU for this particular system;

• Create a calibration tone in the workstation (a sine wave) at that level, and adjust the output of the workstation (or the input trims of the analog console) so that that tone registers 0 VU on the console’s meters. (When doing this, keep all other faders and trims in both the workstation and the analog desk at unity gain.)

Now you can use the console’s VU meter as a reference to keep your digital levels compatible with the analog world. And if the workstation has a plug-in or VU-type meter programmed to respond to average levels, that could be calibrated to match the analog meter, giving you a suitable analog reference within the digital domain.

For a long time, there was no official digital level designated as the standard equivalent to 0 VU (+4 dBu). People argued over whether such any “official” calibration level should be set quite low (i.e. around –20 dBFS) to allow for the most headroom that might be required, or set significantly higher (i.e. around –16 or even –12 dBFS), to maximize digital resolution whenever it was possible to mix at a hotter digital level.

Currently, many people use a level of –14 dBFS as a kind of standard. Even though this –14 dBFS doesn’t allow for as much headroom, it’s a decent compromise given the nature of modern pop recordings (which are heavily compressed and limited), a compromise that doesn’t keep operating levels uncomfortably low in many workstations. But still, when interfacing the analog and digital worlds, I’d make no assumptions about any kind of calibration, and keep a careful eye on all meters when doing any kind of analog-to-digital transfer.

Automation

Besides adapting to different levels and metering, another significant change to my mixing routines has been my approach to mix automation. Now, I started out way back in the days when automation consisted of a half-dozen engineers, musicians, and assistants crowded around the console, each with a couple of fader moves to make in real time while the mix was bounced down—if one person screwed up, we’d all have to try it again from the top!

As console automation systems gradually grew from simple fader and mute settings to complete dynamic control and full recall capabilities, the one constant was that to build up an automated mix, you grabbed a fader or three and pushed ‘em up and down while the music played, section by section, over and over.

When I moved over to the virtual mixer environment, like everyone else I retained that sensibility, craving the sexy moving-fader control surfaces (that were available then only for the really big-ticket workstations), so I could continue to work within that familiar paradigm. But, by the time those control surfaces had become more universally affordable, I realized I’d gotten so used to a different approach that I no longer felt such a need for a fistful o’ faders as I had in the past.

Most workstations offer at least two ways to enter mix automation data. The traditional approach is via faders, either virtual onscreen ones or external physical faders. The onscreen faders are moved with the mouse, and so only one can be adjusted at a time, which most people coming from console mixing find limiting, compared to the ability to get two or three faders at once under your fingers on a hardware mixing device.

Graphic automation

But there’s another way to go in a virtual mix environment, and that’s entering the automation moves as graphic curves over the track display. These visual curves show up as you move the faders when recording automation data, but they can also be drawn in by hand. This can be a pretty unfamiliar way of building up a mix for someone used to a more tactile, realtime method, but for anyone who has ever done any graphics work on a computer, drawing in curves can be a very efficient and comfortable way to enter relatively precise data in less time than it might take to “play” the moves in by hand while the track runs.

Of course, some automation moves require that you hear the mix as you do them, but, as I came to realize, a lot of basic utilitarian mix adjustments (like matching levels on punch-ins or slightly bumping a track’s balance from verse to chorus) can be easily entered graphically. The more I did this, the more I came to learn just how much of a change I typically wanted in various mix situations—eventually I realized that I could build up a lot of the bread-and-butter moves of a mix just as quickly by drawing the automation in, and I wouldn’t be as worn out hearing the track over and over as I would entering that data in realtime. A few quick playbacks as I go along to hear what I’ve entered, a couple of additional tweaks, and I’m usually good to go.

Compression

One more change I’ve made in mixing of late has been to stop using any bus compression or limiting on the mix—in fact, I’ve also drastically reduced the amount of compression I use on drums. The reason is the current trend of mastering CDs at extremely hot levels—to achieve these levels, large amounts of compression and limiting are applied at the mastering stage. I won’t get into a discussion of the overall merits or disadvantages of this widespread practice here (we talk about the Loudness Wars in the “On Mastering” section of this library!), only how it impacts on decisions made earlier on in the mixing stage.

One of the ways to add punch to a mix is to add a bit of compression overall, on the stereo bus. A judicious amount at this point can bring up the quieter parts of the mix, and overall make things a bit fuller and more “in-your-face”. Likewise, some bus-limiting of transients can fatten up percussive sounds (like drums), though at the expense of transient impact.

But sometimes problems can develop when that mix hits the mastering house. The mixer may achieve just the amount of compression and limiting he/she wants on the outputs, but during mastering there will likely be more added (sometimes for different reasons)—all of sudden what sounded good initially might now be sounding overdone. Punchy and fat can become flabby and overly thick, and often the mix can lose its crispness and snap.

Many people, when mixing, compare their mixes to commercial recordings which have already been mastered, and try too hard to emulate the dense sound and hot levels on these discs. Even if a certain amount of compression and limiting is warranted, if too much (or the wrong type of) dynamic processing has been applied in the mix stage, it becomes difficult or impossible to correct for later.

Over the last couple of years that I’ve been doing a little mastering, I’ve found that by leaving out the bus compression and limiting to that final stage, it was often much easier to achieve consistent results across several tracks on an album, and focusing on overall dynamics separately from other mix considerations invariably helped me achieve cleaner and clearer masters.

I also realized that some of the compression I was applying to the drums, specifically, was really an attempt to achieve the kind of density that I was hearing in various commercial reference CDs, and instead leaving the drums mostly uncompressed and popping in the mix allowed them to retain more impact when the inevitable mastering dynamics had been applied and the level of the recording had been cranked up to modern standards.

So long

Well, that’s all there’s room for here—hopefully anyone who’s testing the waters of the virtual mixing environment will find some of these observations helpful, or at least food for thought. And if you are stepping from the warm and fuzzy world of analog into the all-digital domain, don’t be afraid to try something that at first feels uncomfortable or unfamiliar—you may find that, rather than putting a crimp in your mixing style, sometimes a little change can be a good thing.